Well, it’s October again, which means we are celebrating American Archives Month—and in the non-Archives world, Halloween! Something fun about living in an old city is discovering history around every corner. Tourists flock to St. Augustine for its “ancient” feel. And any city steeped in time comes with echoes of generations—and tales of the paranormal: ghosts, hauntings, and unexplained phenomena. While these usually begin with a kernel of truth, it is my experience that the facts are often overshadowed by sensationalized tales fit for Hollywood. The more thrilling the tale, the more captive the audience, the taller the legend grows.

Enter the “Strange Case of the Exploding Bishop.”

The story goes like this: The first bishop of St. Augustine, Bishop Augustin Verot, P.S.S. (Society of St. Sulpice), died suddenly in June. His body was laid in a pit lined with sawdust and ice, though some versions say he lay in state at the Cathedral. Subject to intense heat over successive days, the bishop’s decaying body exploded. One version claims this sensational event occurred over the mourners during his funeral. It ends with remnants of the bishop being retrieved and given a hasty burial in the Cathedral Cemetery.

A Game of Historical Telephone

Thanks to records in the Diocesan Archives, we can examine the events around and after Bishop Verot’s death to see how the legend matches up with reality.

The Bishop’s Death

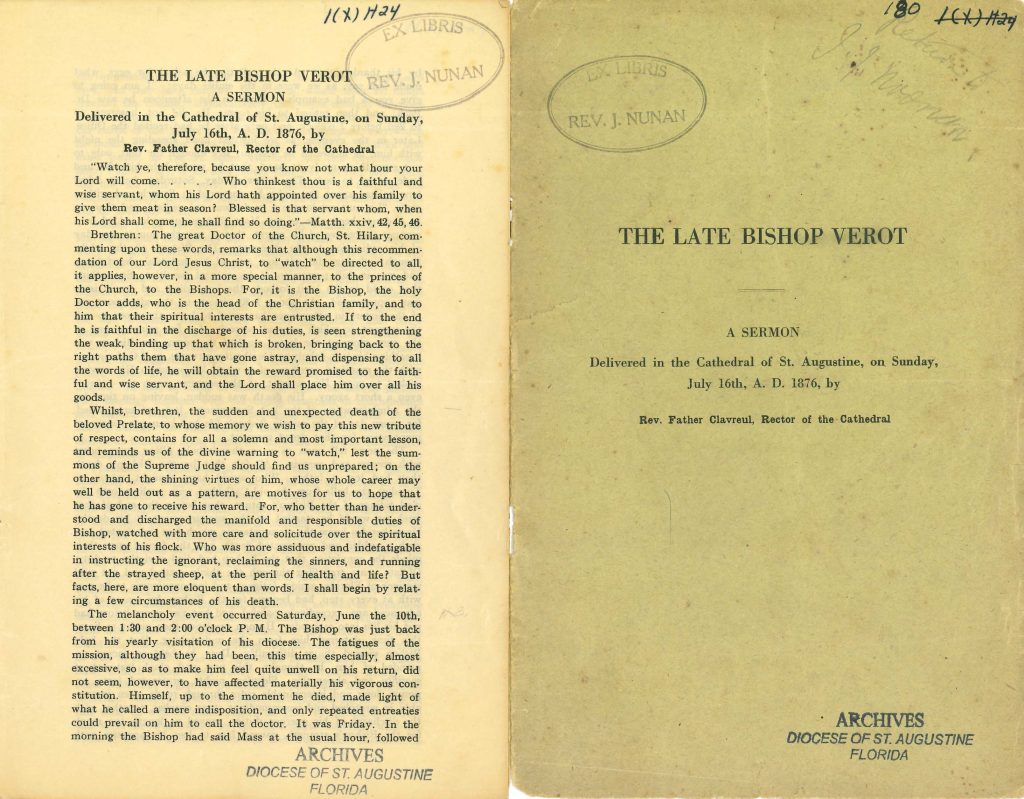

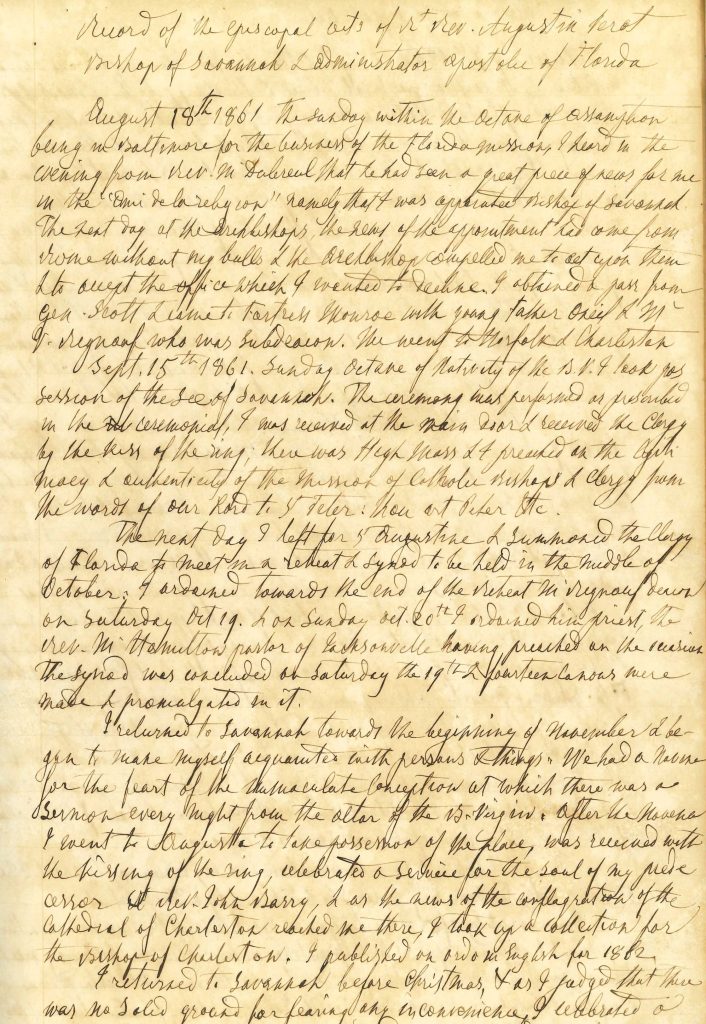

In a memorial sermon some weeks later, Father Clavreul described circumstances around Bishop Verot’s sudden death. It was Friday, June 9, 1876, and Bishop Verot had just returned from his yearly visitation of the diocese. This particular trip caused excessive fatigue for the 71-year-old bishop.

At the time, the Diocese of St. Augustine ranged from the Florida-Georgia state line west to the Apalachicola River (the western boundary of modern-day Franklin, Liberty, and Gadsden counties) and south to Key West. Traveling in the 19th century was far from the comfortable experience we enjoy today. The bishop’s diary chronicles many arduous trips lasting months on end. He was well acquainted with the vast territory. Often conveyed by mule, horse and buggy, stagecoach, ferry, and sometimes on foot, the bishop visited his rural churches and Catholic missions all over the state, lodging with Catholic families or inns when available, and was known to fast on the road.

The day before his death, despite exhaustion, the bishop attempted to keep a normal schedule, fully intending to continue his visitation after a brief respite in St. Augustine. He said Mass in the morning, but Father Clavreul persuaded him to allow Dr. Peck to visit early that afternoon. The bishop retired to bed early, refusing to allow anyone to sit with him through the night. When checked on the next morning, he confessed his inability to celebrate the required morning Mass in private and described his night as “long with pain that keeps watch.” Though he was in a cheerful mood and “in full possession of his mental faculties,” the bishop stayed in bed all Saturday the 10th. That afternoon, to everyone’s complete surprise, Bishop Verot died suddenly between 1:30 and 2:00 p.m.

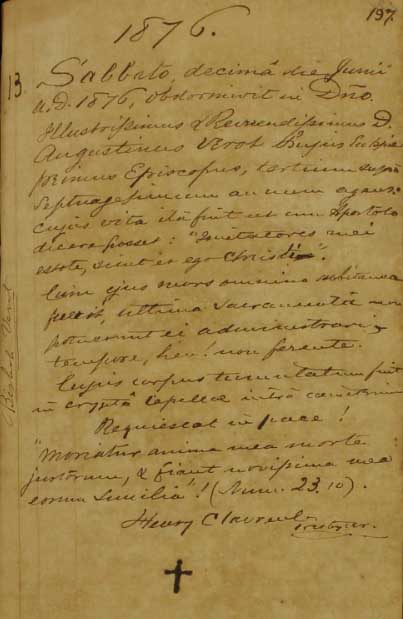

A sad note accompanies his entry in the Cathedral death register:

“…On account of his most sudden death there was not time to administer upon him the last sacraments, whose body was interred in the crypt of a chapel inside the cemetery. Rest in peace!”

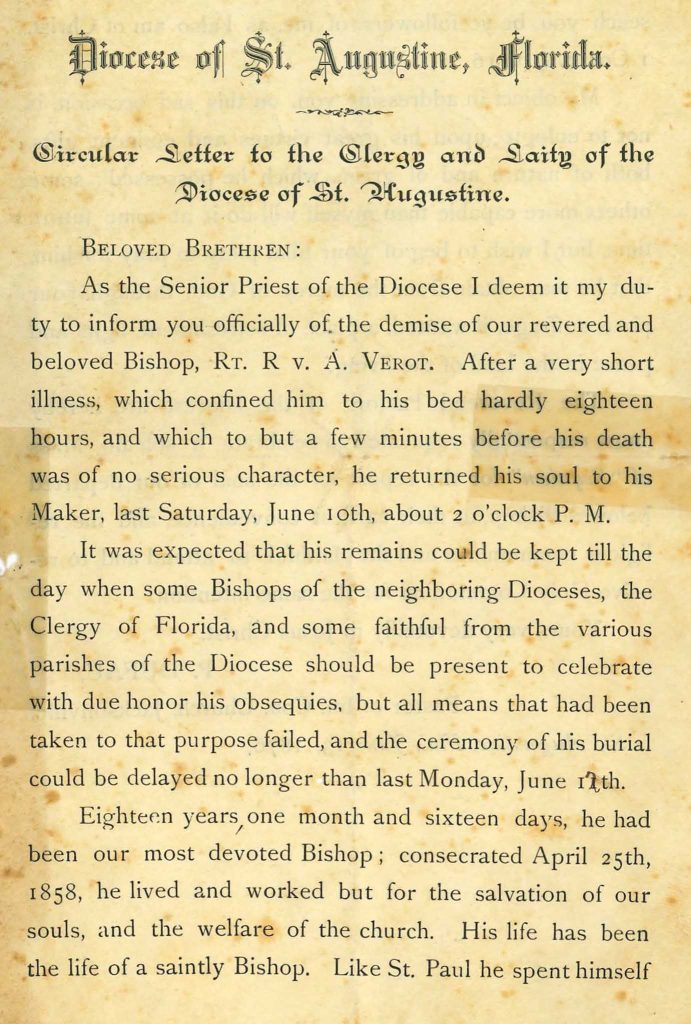

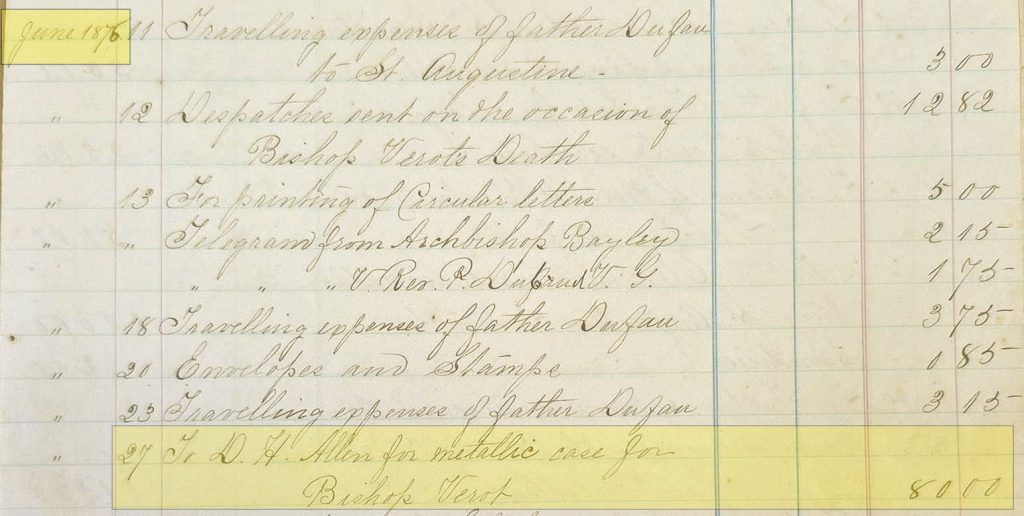

Following Bishop Verot’s death, Father Peter Dufau, appointed diocesan administrator, distributed a circular letter announcing this sudden event and requesting all parishes say a Mass of Requiem for the bishop’s soul. Father Dufau also noted, “It was expected that his remains could be kept till the day when some bishops of neighboring dioceses, the clergy of Florida, and some faithful from the various parishes of the diocese should be present to celebrate with due honor his obsequies, but all means that had been taken to that purpose failed, and the ceremony of his burial could be delayed no longer than last Monday, June 12.”

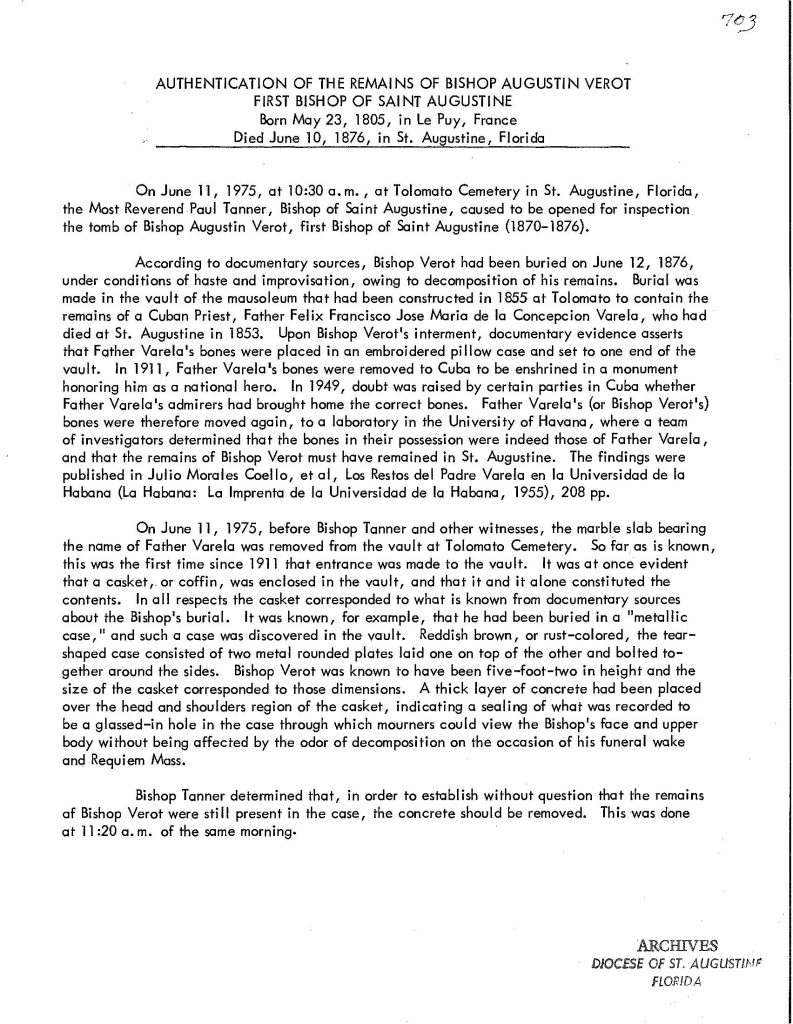

Historian Michael Gannon attributes the hasty burial to melting ice, which did not last long. In his 1976 report, Authenticating the Remains of Bishop Verot, Gannon mentions that the metal coffin in which the bishop was interred had a glass window so that “…mourners could view the Bishop’s face and upper body without being affected by the odor of decomposition.”

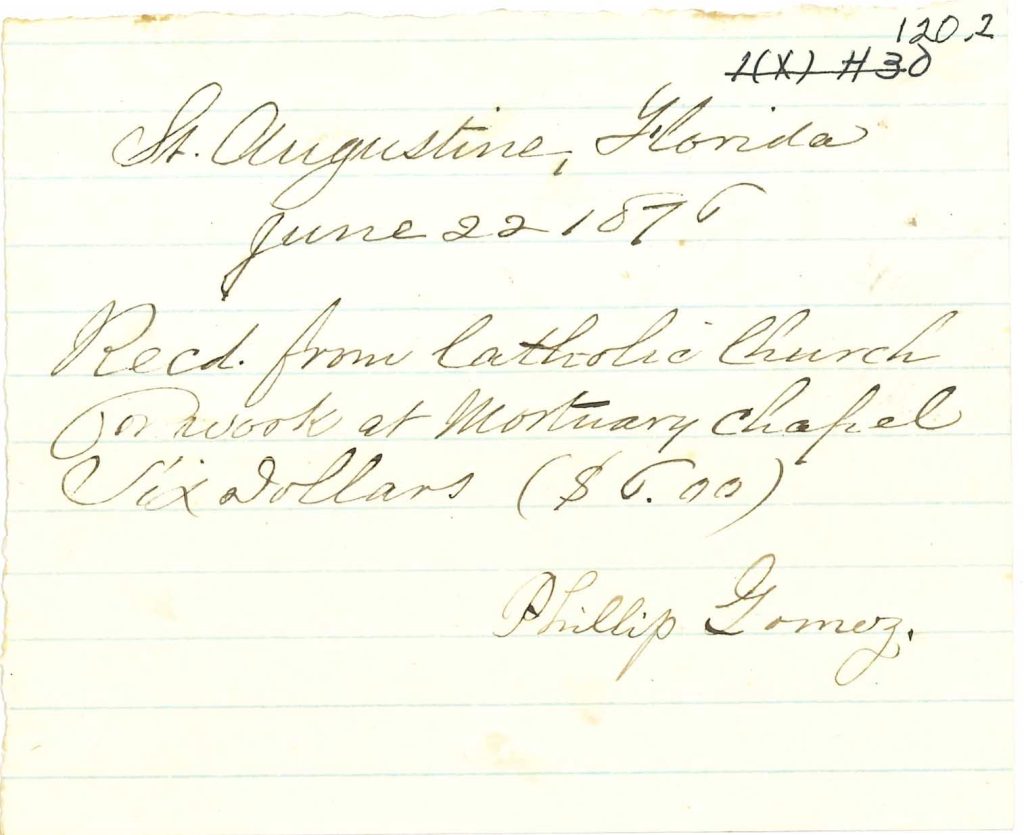

So, on Monday, June 12, Bishop Augustin Verot was laid to rest in the mortuary chapel vault built for Father Felix Varela about 20 years earlier. Local St. Augustinians remember Father Varela’s bones being gathered into a pillowcase and set at the foot of the vault to make room for Bishop Verot’s metal coffin.

Opening Bishop Verot’s Tomb

But that’s not the end of the story. The bishop’s tomb was opened three more times in the subsequent 100 years.

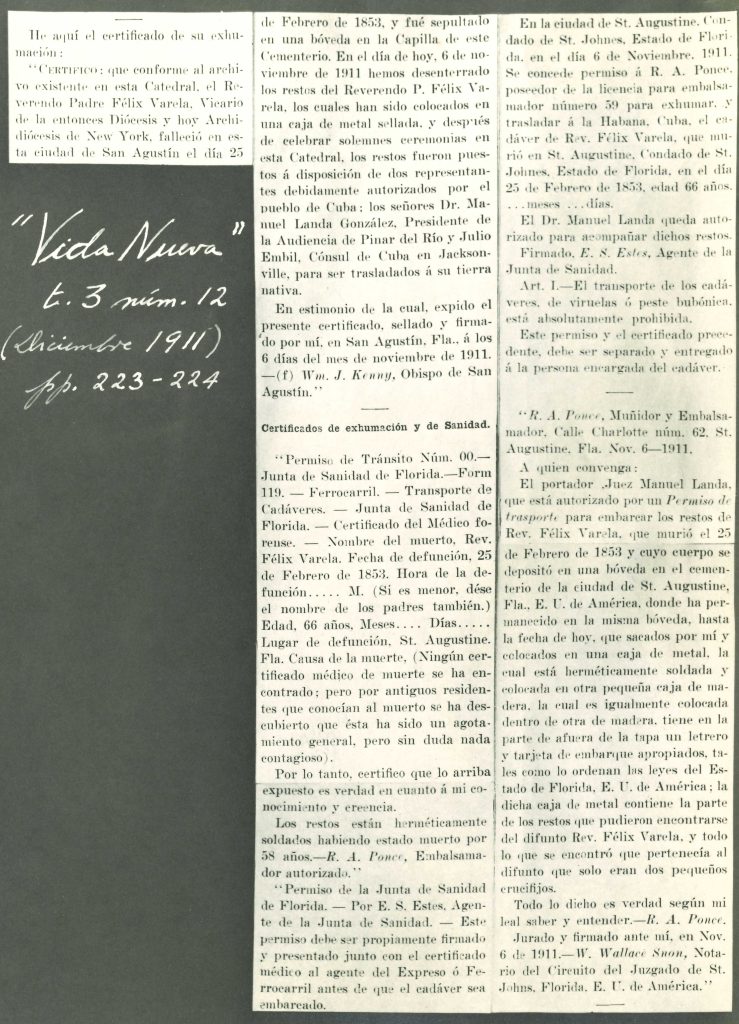

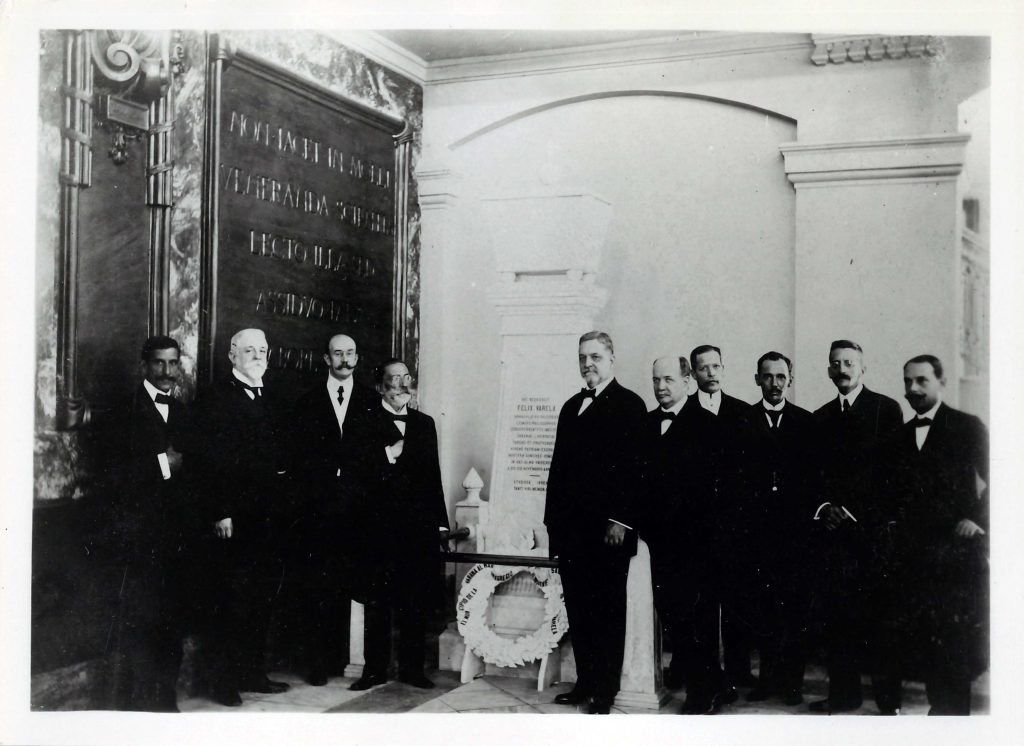

In November 1911, the decision was made to repatriate Father Varela’s remains to his native country. On November 6, Bishop William Kenny certified that Father Varela’s bones were disinterred and given to the Consul of Cuba for onward translation to the University of Havana. St. Augustine’s bishop described them as “those which had been collected in a sealed metal box.”

Fast forward to 1949. Doubts arose as to whose remains were transferred from St. Augustine to the University of Havana—Father Felix Varela’s or Bishop Augustin Verot’s. The confusion likely came from Bishop Kenny’s 1911 certification. It was widely documented that Bishop Verot was buried in a sealed metal casket, and those present remembered Father Varela’s bones gathered into a pillowcase at the foot of the vault. Imagine the anxiety this question caused! Had someone accidentally sent St. Augustine’s first bishop to Cuba? Bones from the ossuary at the University of Havana were tested and confirmed to be Father Varela’s. However, rumors clearly persisted.

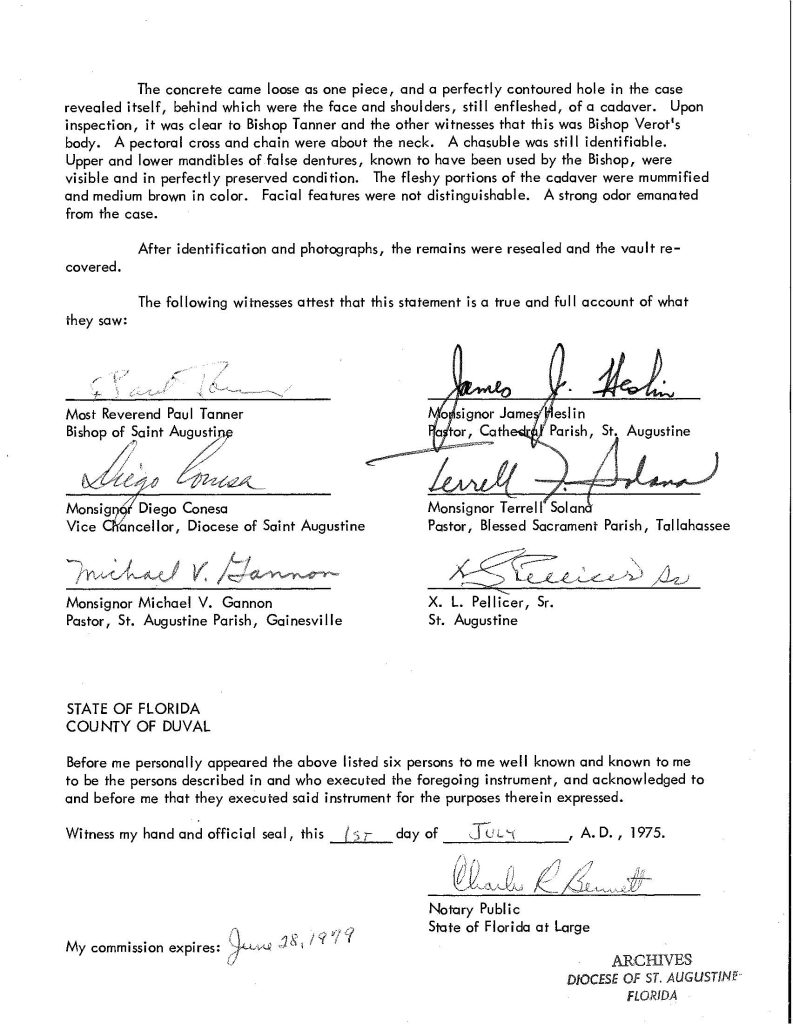

This brings us to June 1975. Probably in response to the rumors, Bishop Paul Tanner authorized the authentication of Bishop Verot’s remains. On June 11, the bishop and five witnesses gathered to open the chapel vault. They observed a metal casket, the correct size for Bishop Verot (5’2”), with a thick layer of concrete over the head and shoulders of the casket. Desiring to establish Bishop Verot’s identity without question, Bishop Tanner ordered the concrete sealing the glass viewing hole removed. This act broke the viewing window. While it made Bishop Verot easily identifiable, Gannon explains that “…a strong odor emanated from the case.”

In 1986, the diocese received a $25,000 donation from St. Augustine locals and a Georgia couple to build a memorial tomb for the bishop in a more prominent spot at the center of Tolomato Cemetery. On January 22, 1988, the bishop’s remains were moved from the mortuary chapel. Although Gannon’s memo does not detail how securely Bishop Verot’s 99-year-old remains were resealed in 1975, the odor suggests it was not done thoroughly. When the bishop’s vault was opened, the stench was so pungent it cleared spectators out of the cemetery, making some violently ill. The event remains vividly etched in the memories of those who were present.

So, Wait, the Bishop Never Exploded?!

Nope. Not even a little bit.

I can see potential roots of this myth: the bishop being packed on ice and hastily buried, and the strong odors that emanated from his cracked casket in 1975 and 1988. But no—the bishop never exploded.

Ghost Stories Dehumanize the Man

In the myth of the exploding bishop, the thing I have the hardest time with is how it distills him down to one horrifically gruesome incident that never happened. People recall this myth rather than the lasting and significant effect Bishop Verot had on Florida, Georgia, the South, and the Catholic Church.

Bishop Augustin Verot (1805–1876) was a pioneer of the Catholic South. Born in France and ordained to the Sulpician Order, he served as a missionary to the United States. His early years as a priest were spent as a teacher in Maryland at the Sulpician Seminary, an author, and pastor of St. Paul Catholic Church in Ellicott City. It was from there that he was called to be the first vicar of a newly established Catholic territory in Florida (us!). He went on to minister to all of Florida and, in 1861, was also given the Diocese of Savannah to administer. At the time, Savannah’s see encompassed the whole state of Georgia.

In his diary, the bishop detailed his long journeys from North Georgia to the Florida Keys during the Civil War. He negotiated his way across Union and Confederate lines, demanded reparation for sacked southern churches, and discovered Camp Sumter (Andersonville Military Prison Camp near Americus, Ga.), the deadliest POW camp of the Civil War. During Reconstruction, after receiving his official pardon, Bishop Verot went on fundraising trips through the North to support rebuilding churches destroyed by the war.

In 1870, the Diocese of St. Augustine was established. When given the opportunity to remain the third bishop of Savannah or become the first bishop of St. Augustine, Bishop Verot opted for Florida, saying that his work began here and this is where he wanted to finish it. Our first bishop grew the diocese from six churches, three priests, and no religious to 11 priests, 20 churches, 70 mission stations, six convents, two seminarians, and approximately 10,000 Catholics. He brought religious communities to educate the children of his territory, both white and those of color, establishing the foundation of Florida’s parochial school system. He wrote a catechism that served as a model for the better-known Baltimore Catechism. He re-established Church ownership of the earliest Catholic site in North America—the Shrine of Our Lady of La Leche at Mission Nombre de Dios. Bishop Verot also served as one of 47 North American bishops in attendance at the Ecumenical Council of Vatican I, cut short by the Franco-Prussian War. He traveled to Havana, Cuba, and safeguarded the oldest Catholic records from the United States, the parish church of St. Augustine.

So, if you hear the tale of the exploding bishop as tourist trolleys roll by in St. Augustine, feel free to flag one down and set the record straight.